Eggcellent Explorations: Mastering the Art of Egg Gels in Culinary Alchemy

Uncover the secrets of achieving ideal egg gels in cooking. Learn how temperature control and ingredient combinations can yield diverse egg textures.

COOKING BEST PRACTICES

Francesco Feston

10/26/20234 min read

The Versatility of Eggs as Gelling Agents

Egg gels serve as a foundational component in numerous traditional dishes. Eggs are commonly incorporated into culinary preparations because their protein content effectively binds various ingredients. They play a unifying role in bringing together the components of muffin batter, the granules of flour in pasta dough, and the elements of sweet desserts like custard, quiche, or chawanmushi (a savory Japanese egg custard). Additionally, eggs are instrumental in binding forcemeats in certain sausages and meatloaf.

The versatility of eggs as gelling agents is unparalleled in the realm of traditional cooking. They can be gently cooked with constant stirring to create a pourable creme anglaise, or blended and cooked without stirring to form a solid egg custard. Regrettably, conventional cooking texts often fail to provide in-depth explanations regarding the interactions of eggs with other ingredients. Understanding these processes allows you to maximize the use of eggs in your culinary endeavors.

The crucial threshold

It's essential to note that at temperatures below approximately 55°C (130°F), egg proteins will not congeal into a gel network, even if they are maintained at these temperatures for extended periods. This property can be exploited for pasteurizing eggs in their shells, effectively eliminating the risk of salmonella and other egg-borne pathogens, as we'll see in detail in another post. Pasteurized eggs maintain the appearance of raw eggs and possess all the expected physical properties. They can be whipped into meringues, act as emulsifiers in mayonnaise, and fulfill other roles typically associated with "raw" eggs, all without the risk of causing illness. While many individuals safely consume raw eggs, pasteurization is a prudent practice for any eggs intended for raw consumption.

Egg proteins begin forming thermally irreversible gels at temperatures exceeding 55°C (130°F). It's important to bear in mind that egg whites gel at lower temperatures than egg yolks. Therefore, at any given cooking temperature, the egg white consistently sets more firmly and seems more fully cooked than the yolk, each with its distinct texture.

As you become more acquainted with the specific solidification temperatures of egg whites and egg yolks, you will be better equipped to tailor your egg cooking techniques to achieve precise outcomes.

A delicate balance: whites and yolks

The primary challenge in cooking a whole egg lies in striking a balance between the doneness of the white and that of the yolk. Achieving thermal equilibrium in a water bath, a combination oven, or a water-vapor oven takes approximately 35 minutes. The cooking time may vary for different egg sizes, with smaller quail eggs requiring about 15 minutes and larger goose eggs taking up to 40 minutes. The timing does not need to be extremely precise since you are cooking until the egg reaches the same temperature as its surroundings.

For those seeking perfect soft-boiled eggs, a two-step process is employed by meticulous cooks. Initially, the egg is cooked for 35 minutes at 60°C (140°F) for a runny yolk or at 64°C (147°F) for a firmer yolk. To ensure food safety, you can pasteurize the eggs by keeping them at these temperatures for an additional 12 minutes. If needed, the eggs can be held at these temperatures for an extended period until you are ready to serve them. Just before serving, a brief plunge in boiling water for 1-2 minutes (for serving in the shell) or 3 minutes (for shelling) creates a thermal gradient within the egg, heating the white to nearly an ideal temperature. This two-stage approach is often more reliable than the standard "three-minute egg" technique.

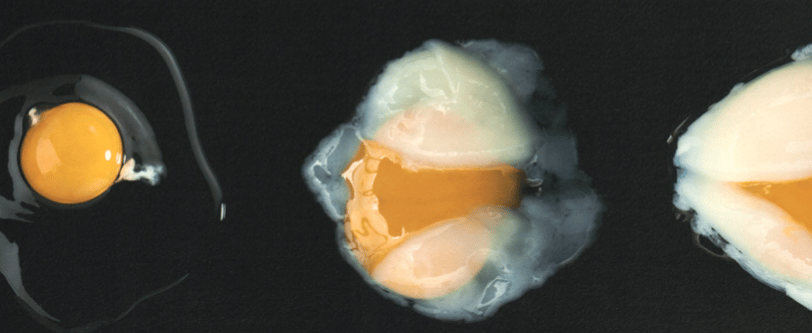

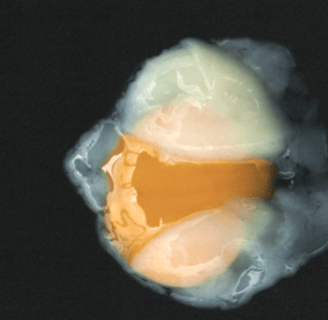

Achieving a perfect sunny-side-up egg in a frying pan is challenging because the white and yolk cook at different rates. No single method can create the ideal conditions for both components simultaneously. Therefore, the white and yolk are cooked separately. First, the white is cooked within egg rings in a nonstick pan placed in a steam oven set to 80°C (175°F). Subsequently, a raw egg yolk is carefully placed in the center of each round of white, and the pan returns to the steam oven at 60°C (140°F) until the yolk is done. This approach results in the ultimate "fried" egg, with the yolk and white cooked at their respective ideal temperatures.

Whole eggs cooked at low temperatures, particularly within the range of 62-65°C (144-149°F), are renowned for their unique, semi-congealed texture. In Japan, they have long been referred to as "onsen tamago" or hot spring eggs. The popularity of this approach in Western cuisine has been promoted by figures such as Herve This and Pierre Gagnaire.

The Texture Spectrum

It's important to note that there is no one-size-fits-all temperature for achieving the desired egg texture, as each one-degree increment from 60°C (140°F) up to 90°C (194°F) produces varying textures, from liquid to brittle and powdery. When other ingredients are introduced alongside eggs, the textures of egg white, egg yolk, and whole mixed eggs are influenced not only by the cooking temperature and duration but also by the quantity and nature of additional materials (liquid and solid) added. Consequently, the composition of mixed egg gels spans a spectrum, from scrambled eggs and omelets with minimal additional fluid and fat to lighter custards and flans that rely on the gelling properties of egg proteins to hold together heterogeneous mixtures. As always, personal preferences vary, but these egg gel formulas provide a solid starting point for your own taste experiments.